Million Beyond "Speed"

RICARDO NUNEZ (opens in a new tab) OCT 1 2023If you've heard of Million (from Aiden Bai (opens in a new tab), its creator, or Tobi Adedeji (opens in a new tab)'s React puzzles on Twitter), you've probably been intrigued by the headline: "Make React 70% Faster".

Most developers have the mindset of faster being better for a multitude or reasons, namely SEO and user experience. If I could write plain React and make it as fast or faster than a lot of frameworks like Svelte and Vue (in some cases), then it's a win, right?

However, there are actually a few other reasons why Million optimizes React applications that has less to do with just "speed" and more to do with compatibility, whether with old devices, slow laptops, resource-constrained phones, etc.

Ultimately, what all of this comes down to is memory.

The old meme of a Chrome window with 10 tabs open chugging your old laptop to a halt has a lot more basis in reality than people realize.

If we look at the situations where an app is running really slowly despite being on a good network, it typically has a lot less to do with bandwidth and a lot more to do with memory, and that's what we're taking a look at in this article.

React Without Million

The way that typical React applications work without Million and without a server-side framework like Next.js is that for every component in your JSX, a transpiler (Babel) calls a function called React.createElement() which outputs not HTML elements but React elements.

These React elements actually create Javascript objects, so your JSX:

<div>Hello world</div>turns into a React.createElement() Javascript call that look like this:

React.createElement('div', {}, 'Hello world')Which gets you a Javascript object that looks like this:

{

$$typeof: Symbol(react.element),

key: null,

props: { children: "Hello world" },

ref: null,

type: "div"

}Now, depending on how complex your component tree is, we can have nested objects (DOM Nodes) that go deeper and deeper where the root element's props key has hundreds or thousands of children per page.

This object is the virtual DOM, which ReactDOM creates actual DOM nodes out of.

So let's say we have only three nested divs:

<div>

<div>

<div>

Hello world

</div>

</div>

</div>This would become something that looks more like this under the hood:

{

$$typeof: Symbol(react.element),

key: null,

props: {

children: {

{

$$typeof: Symbol(react.element),

key: null,

props: {

children: {

{

$$typeof: Symbol(react.element),

key: null,

props: { children: "Hello world" },

ref: null,

type: "div"

}

},

ref: null,

type: "div"

}

}

},

ref: null,

type: "div"

}Pretty large, right? Keep in mind, this is only for a nested object with three elements, too!

From here, when the nested object(s) change (i.e. when state causes your component to render a different output), React will compare the old virtual DOM and new virtual DOM, update the actual DOM so that it matches the new virtual DOM, and discard of any stale objects from the old component tree.

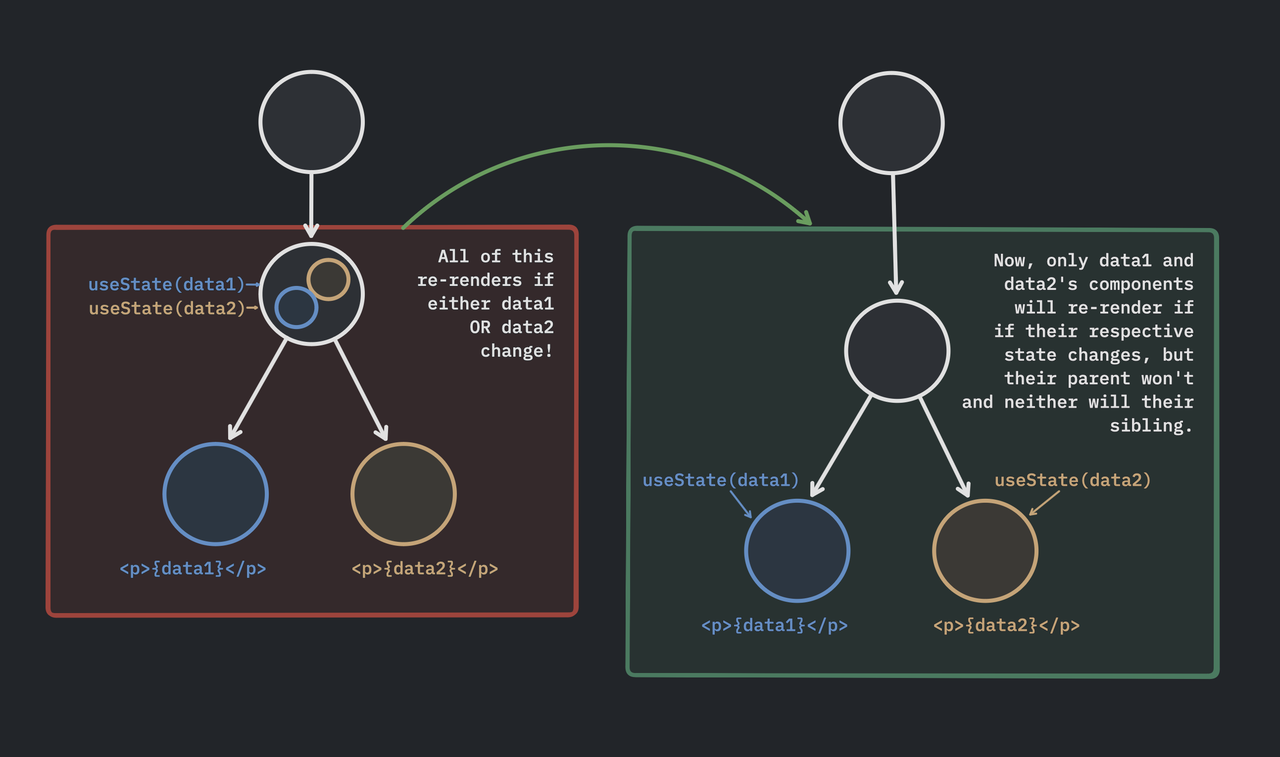

Note, this is why most React tutorials will recommend moving your

useState()oruseEffect()as far down the tree as possible, because the smaller the component is that has to re-render, the more efficient it is to accomplish this comparing process (diffing).

Now, diffing is incredibly expensive compared to traditional server-rendering where the browser just receives a string of HTML, parses it, and puts it in the DOM.

While server-rendering doesn't require Javascript, not only does React require it, but it creates this huge nested object in the process, and at runtime, React has to continuously check for changes which is very CPU intensive.

Memory Usage

Where the high memory usage comes in is in two ways: storing the large object and continuously diffing the large object. Plus extra if you're also storing state in memory as well and using external libraries which also store state in memory (which most people probably are, myself included).

Storing the large object itself is a problem in memory constrained environments, because mobile and/or older devices might not have much RAM to begin with, even less so for browser tabs which are sandboxed with their own small, finite amount of memory.

Ever had your browser tab refresh because it was "consuming too much energy"? That was likely a combination of both high memory usage plus continuous CPU operations that your device couldn't handle along with running these other operations like the OS, background app refreshes, keeping other browser tabs open, etc.

Also, diffing the large component tree means replacing old objects with new objects whenever the UI updates along with tossing the old objects away to the garbage collector, repeating the process constantly throughout the lifetime of the application. This is especially true for more dynamic, interactive applications (a.k.a. React's main selling point).

As you can see, the diffing process for even a simple component where you just change one word in a div means an object for garbage collection to get rid of. But what happens if you have thousands of these nodes in your object tree and many of them rely on dynamic state?

As you can see, the diffing process for even a simple component where you just change one word in a div means an object for garbage collection to get rid of. But what happens if you have thousands of these nodes in your object tree and many of them rely on dynamic state?

Immutable object stores used for state management (like with Redux) tax memory even more by continuously adding more and more nodes to their Javascript object.

Because this object store is immutable, it'll just continue to grow and grow, which further limits the memory available for the rest of your app to use for things like updating the DOM. All of this can create a sluggish, buggy-feeling experience for the end-user.

V8 and Garbage Collection

Modern browsers are optimized for this, though, right? V8's garbage collection is incredibly optimized and runs very quickly, so is this really a problem?

There are two problems with this take.

- Even if garbage collection runs quickly, garbage collection is a blocking operation, meaning it introduces delays (opens in a new tab) in subsequent Javascript rendering.

-

The larger the objects are that have to be garbage collected, the longer these delays take. Eventually, there comes a point where there's so much object creation going on that garbage collection needs to run over and over again to free up memory for these new objects, which is often the case when your React app is open for a decent amount of time.

-

If you've ever worked on optimizing a React app and left it open for a couple of hours, and you click a button only for it to take 10+ seconds to respond, you know this process.

- Even if V8 is highly optimized, React apps often aren't, with event listeners often not being unmounted, components being too large, static portions of components not being memoized, etc.

- All of these factors (even if they are often bugs and/or developer mishaps) increase memory usage, and some (like non-unmounted event listeners) even cause memory leaks. Yes, memory leaks. In a managed memory environment.

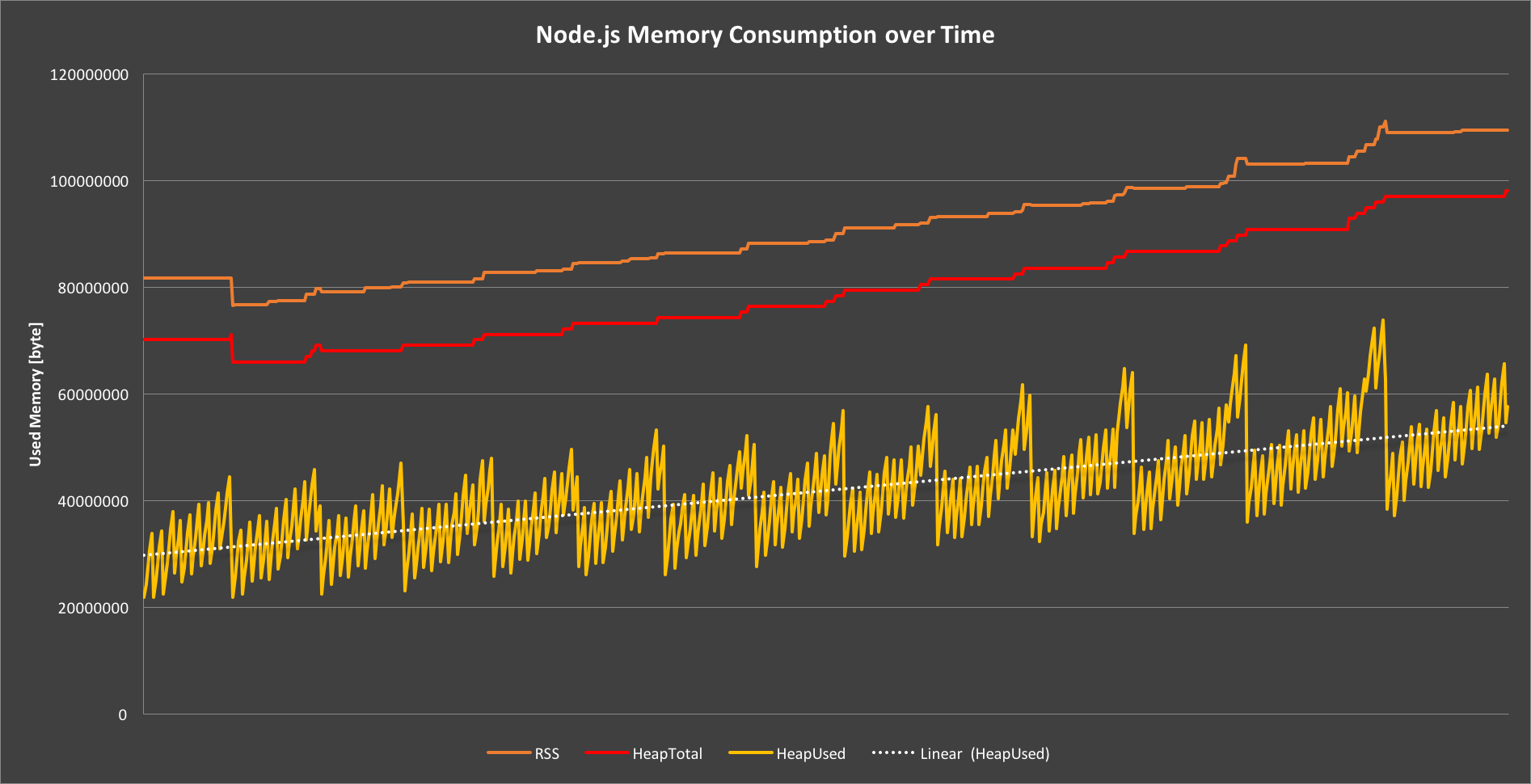

Dynatrace has a great visualization of a Node JS app's memory usage over time when there's a memory leak. Even with garbage collection (the downward movements of the yellow line) getting more and more aggressive towards the end, memory usage (and allocations) just keeps going up.

Dynatrace has a great visualization of a Node JS app's memory usage over time when there's a memory leak. Even with garbage collection (the downward movements of the yellow line) getting more and more aggressive towards the end, memory usage (and allocations) just keeps going up.

Even Dan Abramov mentioned in a podcast (opens in a new tab) that Meta engineers have written some very bad React code, so it isn't difficult to write "bad" React, especially given how easy it is to create memory in React with things like closures (opens in a new tab) (functions written inside of useEffect() and useState()), or the necessity for Array.prototype.map() to loop over an array in JSX, which creates a clone of the original array in memory.

So it's not that performant React is impossible. It's just that it's often not intuitive how to write the best performing component, and the feedback loop of performance testing often has to wait for real-world users with a variety of browsers and devices.

Note: high performance Javascript is possible (I highly recommend this talk from Colt McAnlis (opens in a new tab)), but it's also difficult to achieve, because it requires things like object pooling (opens in a new tab) and static arraylist allocations to get there.

Both of these techniques are hard to leverage in React which is componentized by nature and typically doesn't promote the usage of a large list of recycled global objects (hence Redux's large, immutable, single object store for example).

However, these optimization techniques are still often used under the hood for things like virtualized lists which recycle DOM nodes in large lists whose rows go out of view. You can see more of these types of React-specific optimization techniques (specifically for low-end devices like TVs) in this talk by Seungho Park from LG (opens in a new tab).

React With Million

Keep in mind that even though memory constraints are real, developers are often conscious of the amount of tabs or apps open while running their dev server, so we often won't notice them apart from a few buggy experiences that might prompt a refresh or a server restart in development. However, your users will probably notice more often than you, especially on older phones, tablets, laptops, since they aren't clearing their open apps/tabs for your app.

So what does Million do differently that solves this problem?

Well, Million is a compiler, and while I won't go into everything here (you can read more about the block DOM and Million's block() function at these links), Million can statically analyze your React code and automatically compile React components into tightly optimized Higher Order Components (opens in a new tab) which are then rendered by Million.

Million uses techniques closer to fine-grained reactivity (shoutout Solid JS (opens in a new tab)) where observers are placed right on the necessary DOM nodes to track state changes among other optimizations, rather than using a virtual DOM.

This allows Million's performance and memory overhead to be closer to optimized vanilla Javascript than even performance focused virtual DOMs like Preact or Inferno, but without having an abstraction layer on top of React. That is to say using Million doesn't mean moving your React app to use "React-compatible" libraries. It's just plain React that Million itself can automatically optimize via our CLI.

Keep in mind, Million isn't suitable for all use cases. We'll go into where Million does/doesn't fit in later on.

Memory Usage

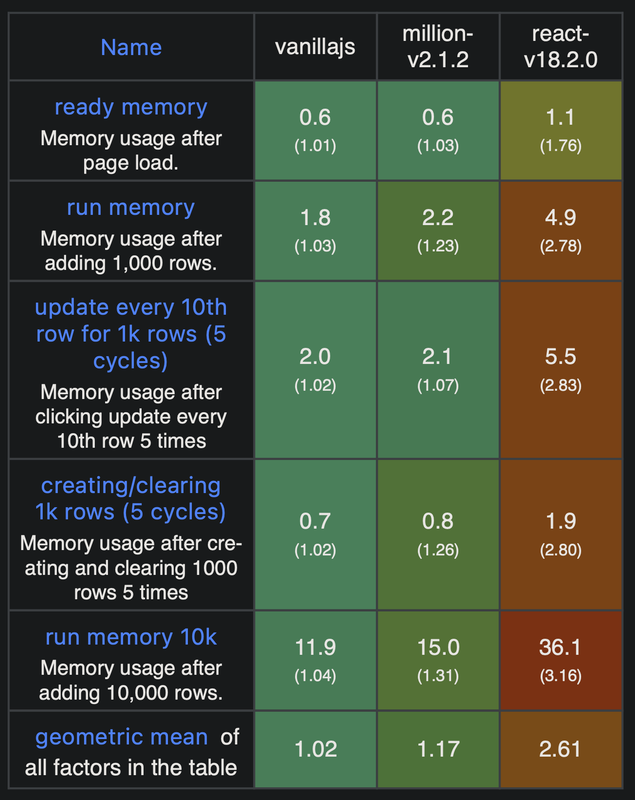

In terms of memory usage, Million uses about 55% of the memory that React does on standby after the page loads, which is a substantial difference. It uses less than half the memory that React does for every single operation otherwise tested by Krausest's JS Framework Benchmark (opens in a new tab), even on Chrome 113 (we're currently on 117).

The memory hit you'd take by using Million compared to using vanilla Javascript would be at most about 28% higher (15MB vs. 11.9MB) when adding 10,000 rows to a page (the heaviest operation in the benchmark), whereas React would use about 303% to complete the same task vs. vanilla Javascript (36.1 MB vs. 11.9 MB).

Couple that with the total operations your app is completing over its lifetime, and both performance and memory usage will vary dramatically when using purely a virtual DOM vs. a hybrid block DOM approach, especially once you consider state management, libraries/dependencies, etc. Of course, in Million's favor.

Wait, But What About _?

As with everything, there are tradeoffs when using Million and the block DOM approach. After all, there was a reason that React was invented and there are definitely still reasons to use it.

Dynamic Components

Let's say you have a highly dynamic component in which data is frequently changed.

For example, maybe you have an application which is consuming stock market data, and you have a component that displays the most recent 1,000 stock trades. The component itself is a list that varies the list item component that's rendered per stock trade depending on whether it was a buy or sell.

For simplicity, we'll assume it's already prepopulated with 1000 stock trades.

import { useState, useEffect } from "react";

import { BuyComponent, SellComponent } from "@/components/recent-trades"

export function RecentTrades() {

const [trades, setTrades] = useState([]);

useEffect(() => {

// set a timer to make this event run every second

const tradeTimer = setInterval(() => {

let tradeRes = fetch("example.com/stocks/trades");

// errors? never heard of them

tradeRes = JSON.parse(tradeRes);

setTrades(previousList => {

// remove the amount of elements returned from

// our fetch call to stay at 1,000 elements

previousList.slice(0, tradeRes.length);

// add the most recent elements

for (i, i < tradeRes.length, i++) {

previousList.push(tradeRes[i]);

};

return previousList;

});

}, 1000);

return () => clearInterval(tradeTimer);

}, [])

return (

<ul>

{trades.map((trade, index) => (

<li key={index}>

{trade.includes("+") ?

<BuyComponent>BUY: {trade}</BuyComponent>

: <SellComponent>SELL: {trade}</SellComponent>

}

</li>

))}

</ul>

)

}Ignoring that there are probably more efficient ways to do this, this is a great example of where Million would not do well. The data is changing every second, the component being rendered depends on the data itself, and overall, there is nothing really static about this component.

If you look at the returned HTML, you might think "Having an optimized <For /> component would work great here!" However, in terms of Million's compiler (barring Million's <For /> component) there is no way to statically analyze the returned list of elements, and in fact, cases like these are why React was first brought about at Facebook (opens in a new tab) (the news section of their UI, a highly dynamic list).

This is a great use case for React's runtime, because manipulating the DOM directly is expensive, and doing so every second for a large list of elements is expensive as well.

However, it's quicker when using something like React, because it will only diff and rerender this granular part of the page vs. something traditionally server rendered which might replace the entire page. Because of this, Million is better suited to handle other static parts of the page to keep React's footprint smaller.

Does that mean only components this extreme should be ignored by Million and use React's runtime? Not necessarily. If your components even lean into this kind of use case where the component relies on highly dynamic aspects like constantly changing state, ternary-driven return values, or anything that can't comfortably fit in the "static and/or close-to-static" box, then Million might not work well.

Again, there's a reason React was built, and there's a reason we're choosing to improve it, not create a new framework!

What Will Million Work Well On?

We'd definitely like to see Million pushed to the limits of where it can be used, but as for right now, there are certainly sweet spots where Million shines.

Obviously, static components are great for Million, and those are easy to imagine, so I won't go too deep into them. These could be things like blogs, landing pages, applications with CRUD-type operations where the data isn't too dynamic, etc.

However, other great use cases for Million are applications with nested data, i.e. objects with lists of data inside. This is because nested data is typically a bit slow to render due to tree traversal (i.e. going through the entire tree of data to find the datapoint your application needs).

Million is optimized for this use case with our <For /> component which is made specifically for looping over arrays as efficiently as possible and (like we mentioned before) recycling DOM nodes as you scroll rather than creating and discarding them.

This is one of the examples where even with dynamic, stateful data, performance can be optimized essentially for free by just using <For /> rather than Array.prototype.map() and creating DOM nodes for each item in the mapped array.

For example:

import { For } from 'million/react';

export default function App() {

const [items, setItems] = useState([1, 2, 3]);

return (

<>

<button onClick={() => setItems([...items, items.length + 1])}>

Add item

</button>

<ul>

<For each={items}>{(item) => <li>{item}</li>}</For>

</ul>

</>

);

}Again, this performance can be gained almost for free with the only requirement being knowing how/when to use <For />.

For example, server rendering tends to cause errors with hydration because we're not mapping array elements 1:1 with DOM nodes, and our server rendering algorithm differs to that of client rendering, but it's a great example of a dynamic, stateful component that can be optimized with Million with a bit of work!

And although this example uses a custom component provided by Million, this is just an example of a specific use cases where Million can work well. However, as we went over before, non-list components that can be stateful and are relatively static work incredibly well with Million's compiler, such as CRUD-style components like forms, CMS-driven components like text blocks, landing pages, etc. (a.k.a. most applications that we work on as frontend developers, or at least I do).

Is It Worth Using Million?

We certainly think so. Lots of people, when optimizing for performance look at the easiest metrics to track: page speed. It's what you can measure right away on pagespeed.web.dev (opens in a new tab), and while that is certainly important, initial page load time usually won't be a big draw on user experience, especially when writing a Single Page Application which is optimized for between-page transitions, not full page loads.

However, avoiding and reducing memory usage where possible is also an incredibly compelling use-case for using Million JS.

If each action that your user performs takes no time to complete and gives them instant feedback, then user experience feels more native, and that's typically where performance issues creep up if you're not careful, because input delay is typically highly influenced by memory usage.

So is it necessary to use a virtual DOM to acheive this? We certainly don't think so. Especially if it means more Javascript to run, more objects to create, and more memory overhead to worry about on lower-end devices.

This doesn't mean Million is a good fit for all use cases, nor will it solve all performance problems. In fact, we recommend to use it granularly, as in some cases (i.e. more dynamic data like we discussed), a virtual DOM will actually be more performant.

But having a tool in your toolbelt that requires almost no setup time or config will certainly get us closer to having React be a much more reliable, performant library to reach for when building an app that will live in the wild, outside of other devs' 8 core, 32GB machines.

Soon, we'll be doing benchmarks on common React templates to see how Million impacts memory and performance, so stay tuned!